In Iloilo City, hundreds of people were forced into prostitution despite health and safety risks amid the pandemic.

By Francis Allan Angelo for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Hazel (not her real name), who works at a mall in Iloilo City, had long known that fellow workers had been forced into prostitution to augment their income. She did not imagine resorting to it herself but during the early months of the pandemic, when lockdowns shut the store that employed her, it was the only option she could turn to.

A single mother of a 10-year-old boy, Hazel said she tried to seek help from relatives but she soon ran out of a lifeline as businesses were closed and almost everyone she knew were also out of work.

She received some assistance from the government, but it was not enough as the lockdowns stretched for months.

When she approached a fellow worker to borrow money, the latter persuaded her to prostitute herself. She gave in out of desperation, she said.

“Hindi na bale ako, pero ‘yung anak ko ang inaalala ko. Baka magutom at magkasakit. Wala akong magawa sa sitwasyon namin (I cannot just think about myself anymore. I had to worry about my son. He might go hungry and sick. I couldn’t do anything),” Hazel said.

Her colleague introduced her to a “client” who paid her P5,000 (about $100) for sex.

It was the first and last time Hazel prostituted herself. She said the experience was demeaning. “Hindi na naulit, ang bigat sa konsensya. Pero ano magagawa ko, may anak ako, e (It didn’t happen again. My conscience couldn’t take it. But what was I going to do? I had to do it for my child),” she said.

Hazel said she knew of other mall workers who were forced into a similar situation to survive the pandemic. This reporter spoke with five others who prostituted themselves to put food on the table, but they declined to elaborate on their experiences.

Hundreds engage in prostitution during the pandemic

Nestor Canong, head of the Iloilo City Task Force on Morals and Values Formation, said prostitution took on a new face during the pandemic as some Ilonggos who had lost their jobs at the height of lockdowns were forced into it.

Before the pandemic, he said most of the documented prostitutes in the city were “imported” or natives of neighboring areas. Many of them decided to stop during the pandemic because of the risk of contracting Covid-19.

For others like Hazel, however, it was their only source of income.

Hazel is what the Social Hygiene Clinic of the Iloilo City Health Office refers to as a “freelance sex worker” or FSW. They work in brothels and the streets, as opposed to Registered Female Sex Workers (RFSW) and Macho Dancers (MD) who work in registered establishments in Iloilo City.

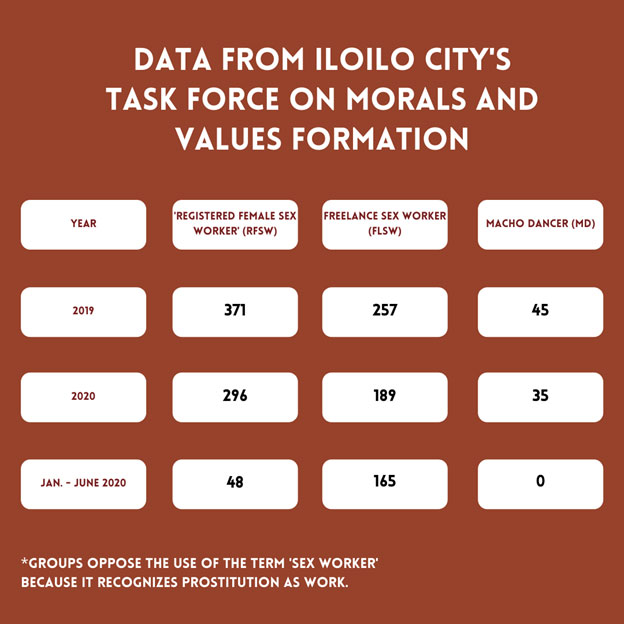

Data from social hygiene clinic show that while the total numbers dwindled during the pandemic, hundreds continued to prostitute themselves despite the risks and amid lockdowns and other restrictions.

The clinic recorded a total of 520 “commercial sex workers” in 2020 when the pandemic began, which was down from the total 673 the clinic recorded the previous year.

The clinic also recorded at least 213 who engaged in prostitution from January to June in 2021.

The term “sex work” is frowned upon by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women-Asia Pacific (CATWA), however. Calling it “sex work” recognizes prostitution as work when, in fact, they are victims, said CATWA executive director Jean Enriquez.

Prostitution is outlawed in Iloilo City under Regulation Ordinance No. 2014-377, but the city government introduced “gray areas.”

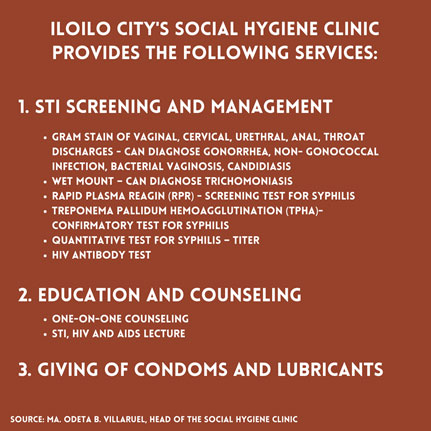

Under its so-called green card policy, the city’s Social Hygiene Clinic issues cards to “commercial sex workers” as proof that they are free from sexually transmitted infections.

Canong said green cards are not permits for engaging in prostitution. It’s one way of protecting not only their personal health but public health as well.

The green cards also facilitate documentation of the city’s prostituted men and wonen and their regular checkup.

There could be more freelance sex workers

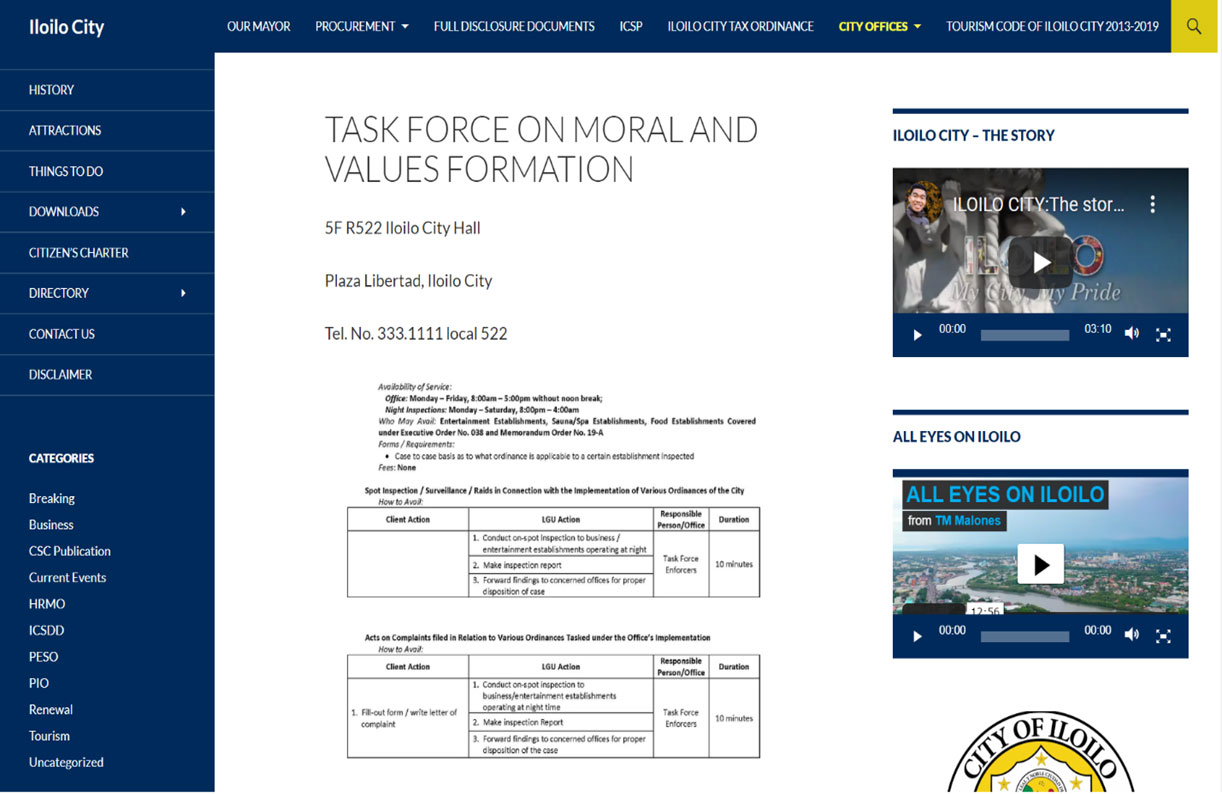

The Task Force on Moral Values and Formation was formed by the city mayor’s office initially to monitor entertainment and food establishments, spas and other businesses that operate at night.

It later began helping prostituted men and women avail themselves of the services of the local hygiene clinic and obtain other opportunities should they decide to seek a different livelihood.

https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/sex-work-and-law-asia-pacific.pdf

During the pandemic, Canong was concerned that more of them were not captured by city data because they went freelance.

“When the pandemic hit, some of the nightclubs and pubs stopped operating and their workers were forced to either go home or become freelance commercial sex workers,” he said.

The data only covered those who went to the social hygiene clinic. “We don’t know how many of them are there on the streets who were not reached or went to the clinic to seek help. That’s why we are actively seeking them out for their own welfare, especially in the time of this pandemic,” he said.

In February 2021, days before Valentine’s Day, the Iloilo City task force rounded up 40 “freelance commercial sex workers” —10 males and 30 females—including a 16-year-old.

Most of them lacked “green cards” from the social hygiene clinic. The card is proof that they are free from sexually transmitted infections.

The apprehended prostitutes were booked and processed at the police station, but were later released for lack of facilities where they could be “remitted.”

The minor was turned over to the City Social Welfare Office for processing and intervention, including counselling, before being sent home.

Canong said those who were apprehended, particularly those who lacked green cards, promised to go to the social hygiene clinic.

In many parts of the Philippines, many prostituted men and women also make the transactions on the Internet, said Arnel Sigue, president of the Anti-Trafficking Legal Advocates Society (ATLAS), a group based in neighboring Bacolod City.

It makes it harder to document them, he added.

Increased risks during the pandemic

During the pandemic, prostituted men and women risked the possibility of contracting the highly transmissible and deadly coronavirus disease on top of the other dangers they regularly faced on the job.

Even as she rationalized what she did for her son’s sake, Hazel remembered how she was so worried that the client might have Covid-19 and infect her. She was tempted to ask him for an RT-PCR result, but didn’t out of fear she might lose the chance to earn.

The task force was concerned that they would trigger an explosion of Covid-19 if they contracted the virus from their clients and then spread it to others.

Many of them were hesitant to avail themselves of free RT-PCR tests offered by the city government. They didn’t want to be forced to undergo quarantine for at least seven days, which could affect their income.

They also faced further discrimination during the pandemic, said Sigue of Atlas

“Before, they were discriminated due to [fears] of sexually transmitted diseases. Now they are further discriminated against due to fear of the virus, which they may contract [from their clients],” Sigue said.

“Their neighbors discriminate against them. They are being ostracized,” he added.

Prostituted men and women continued to be vulnerable to other health risks such as HIV.

There were also reports of human rights abuses and extortion by arresting police officers.

Other countries have introduced workplace health and safety standards for prostituted men and women as well as legal protections from discrimination.

Assistance program on hold

The city government introduced a program where they encourage prostituted men and women to enroll in the alternative learning system (ALS) under a partnership with the Department of Education.

The program was stopped during the pandemic, however. Canong’s team also concentrated on making sure that public and private establishments observed basic health protocols such as safe physical distancing and wearing of face masks.

They also make the rounds of barangays (villages) to enforce these protocols.

The ALS was originally meant to help out-of-school youths obtain a higher level of education. Some sex workers who had stopped schooling were able to enroll in high school or college studies under ALS.

Canong said the ALS program became the foundation of his own plan to provide opportunities to commercial sex workers—an alternative livelihood scheme with the help of the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Tesda).

Through Tesda courses, workers can acquire skills and competencies to start businesses or work here or abroad.

Canong said most of the city’s prostituted men and women wanted better and less self-demeaning opportunities.

“They also told us that they want to earn in more decent ways. They would say ‘Give us better opportunities and we will leave this kind of work.’”

Canong said city officials were preparing to start the program in 2020 but were stymied by the pandemic.

Canong said the mayor’s office could allocate part of its discretionary funds to augment the task force’s budget for projects for commercial sex workers once the situation allowed for face-to-face trainings.

“We really want to help them, especially now during the pandemic, but we had to redirect our priorities to Covid-19 response…. Hopefully, if the situation stabilizes, we can proceed in keeping with current protocols,” he said. END